I recently bought a chessboard so that I can play against my young daughter and we can learn the game together. In a previous essay on chirality (right/left asymmetry) I used the example of boxing to describe the possible combinations of two chiral objects. Looking at my new wooden chessboard, it occurred to me that the game of chess provides a more ready and accessible visual explanation of this phenomenon.

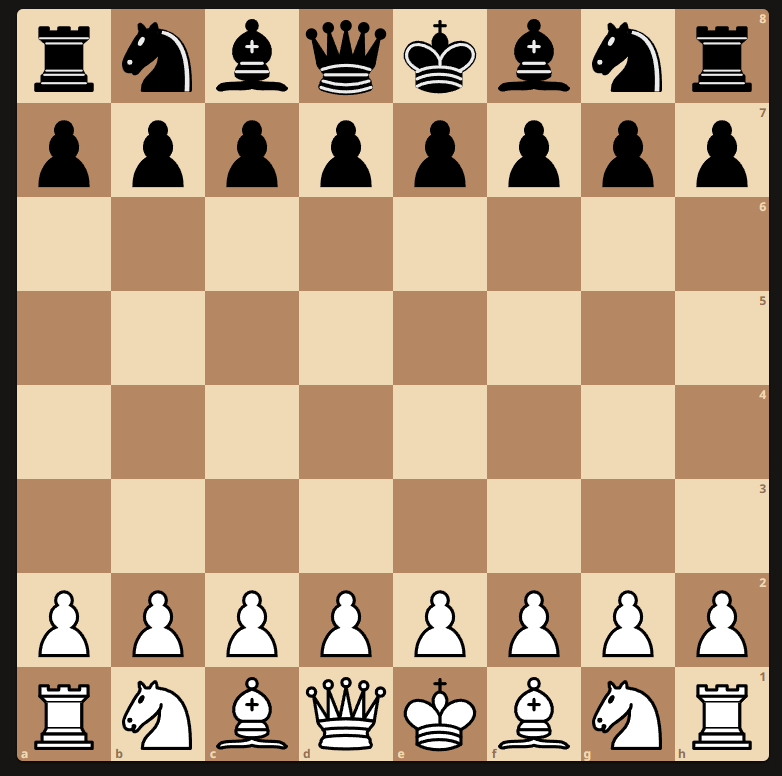

The image above is a chess board set up in the standard way where the queen goes on her own color. Notice first that if not for the king and queen being two different pieces, the game would be very symmetrical. With two kings and no queen, or vice versa, we would be able to cut the board into two equal halves both crosswise and lengthwise (we will ignore the black/white symmetry breaker throughout this discussion for simplicity).*

But the fact that there is a king and a queen means that we can arrange them in two distinct directions relative to the player. The king side could either be to the right or to the left of the queen side. The convention of putting the queen on her own color yields a curious result (as seen above): white and black mirror each other but the king side is to the right for white, while for black the king side is to the left. Remember that the king side is relative to the player’s point of view. So if you are seated behind black, you will see your king to the left of your queen. If you are seated behind white, your king is to your right. Viewed from above, however, the kings and queens proceed along the same direction.

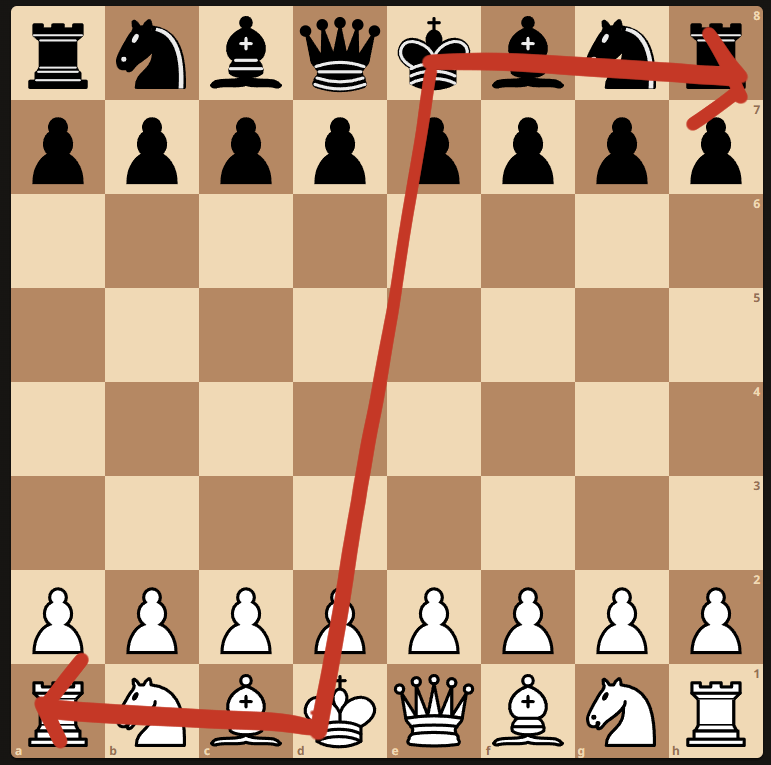

In organic chemistry we have a term for this kind of object: a meso compound. The official definition from the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry for a meso compound is “the achiral member(s) of a set of diastereoisomers which also includes one or more chiral members.” To put this in plain terms, it is, in its simplest form, an object with a right and left handed side brought together so that each side mirrors the other side. Put your right and left hands together in the prayer position and you have formed a meso object. In chemistry, “meso compound” applies only to molecules that exhibit this specific kind of symmetry, but I see no reason not to use it to describe all manner of objects in the world.

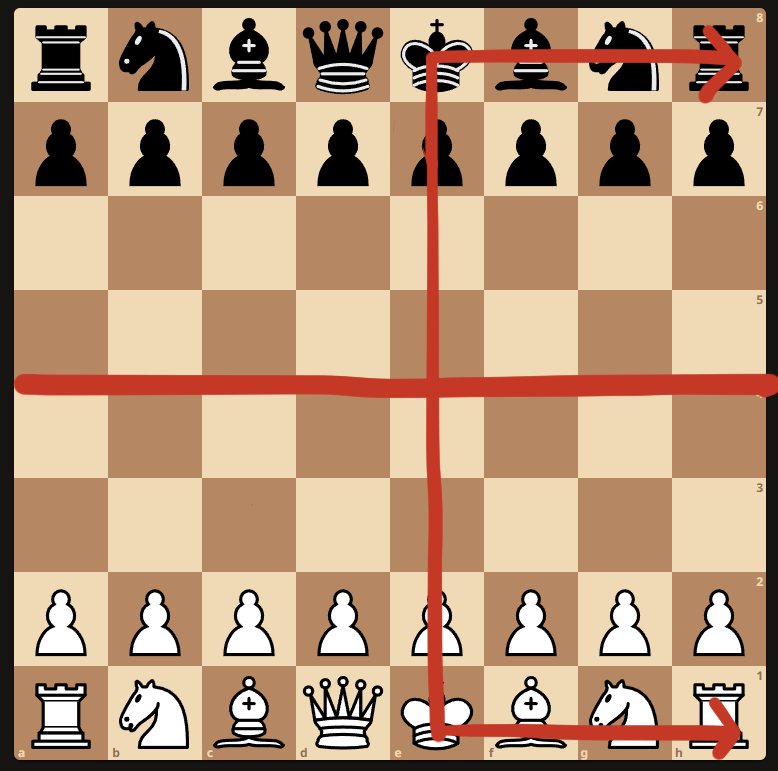

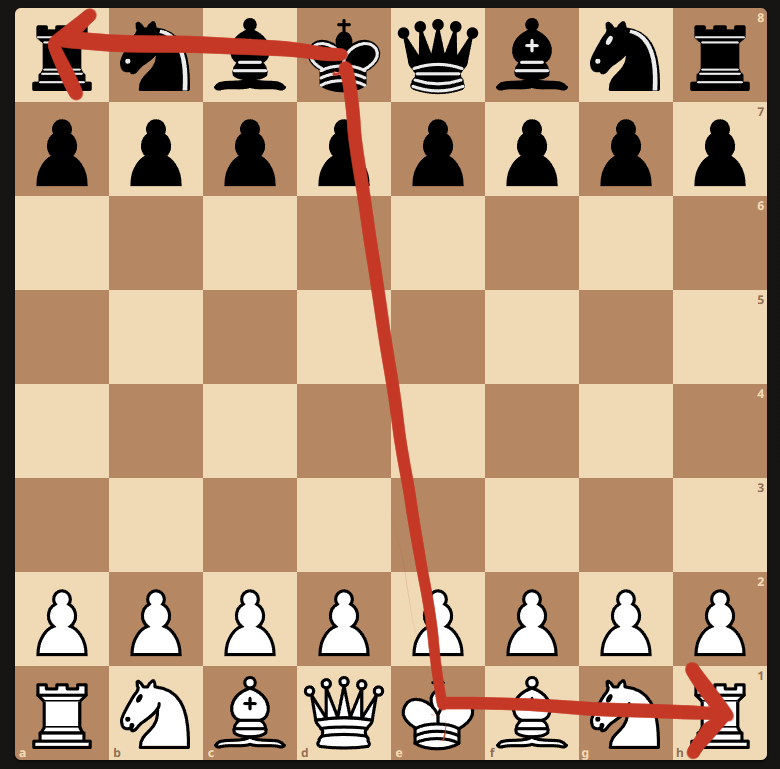

A meso object is, as per the official definition, always a member of a set of possible stereoisomers that include chiral enantiomers. This means that we can rearrange the peices on the board to form a ‘right handed’ chessboard or a ‘left handed’ one. In the image above, the kings and queens have been set so that the king side is to the right from both players’ perspectives. The chessboard is now a chiral object, with both halves having the same right handed ‘turn’. By definition, every chiral object has an enantiomer, and the double-left handed counterpart is shown below.

It is important to point out that there is no inherent difference in the mechanics of play in the two chiral chess boards (right and left) above. But there is an immediate and consequential difference between either of them and the standard ‘meso’ chess board. That difference is that in the chiral setups, each king faces the opposite queen in the same column (or file). In the meso setup, the kings face each other, and the queens face each other. Whenever a pair of stereoisomers differ in their internal mechanics, we call them diastereomers. A pair of chiral objects are enantiomers, and they will always have the same internal mechanics, with the only difference being that the parts are arranged into either a right handed or a left handed turn.

(Chess board images made with lichess.org)

*Note: there is yet another interesting symmetry element, which is the orientation of the board to the players. Note that from the perspective of both players, the white corner could either be on the right side of the board or, by rotating the board 90 degrees before setting it, to the left. It is standard convention to orient the board to the player so that the white corner square is to each player’s right side. This results in the king side being to each player’s right as shown in the first two images when the board follows the queen on her own color convention. Orienting the board so that the white corner square in to each player’s left (by rotating the board by 90 degrees) would result in the king side being on the left of the queen side when the queen is on her own color. Nothing in this essay turns on this difference. The difference it makes is that, for example, the king side rooks could either be on their own color (in the standard setup) or on the opposite color, depending on the rotation of the board.

Leave a comment